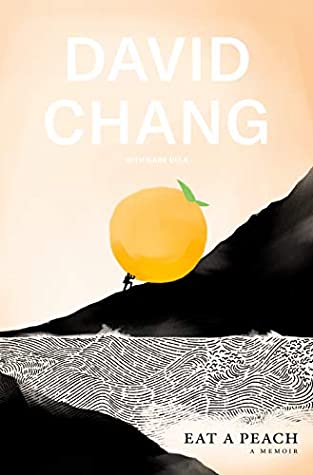

Book review of David Chang’s memoir, Eat a Peach

Despite having eaten at two different Momofukus, I didn’t read David Chang’s memoir, Eat a Peach, because I’m a die-hard fan of his or his Momofuku Empire. I read it because there are so few memoirs written by Asian Americans with a major publisher. It took Chang four years to write what he first thought was going to be a “self-help manual on leadership.’ He was only able to finish when he came to terms with the fact that he was writing a memoir.

Any memoir written by a leader is a de facto book on leadership. By many accounts, Chang has helped change the way Americans eat and he’s a pioneer in a mostly white-led restaurant industry.

This essay highlights parts of the book that resonated with me as an Asian American as well as the leadership lessons he imparts by way of sharing his stories.

In some ways, Chang’s memoir is an antithesis to the Asian as a “model minority,” or the idea that Asians are law-abiding, hard working, highly educated, high-income earners who are also quiet, never angry, not creative, and apolitical. He challenges the notion of Asians as individual contributors and middle managers as opposed to leaders in America.

Throughout the memoir, Chang constantly expresses disbelief at his success. He thought he was experiencing imposter syndrome, and then he realized it was the survivor’s guilt. Few survive the restaurant industry. He managed to not only survive, but succeed on the platform he himself created. “Survivors’ guilt” is felt by those who went through a traumatic experience and survived while others crashed and burned. While he was referring to the restaurant industry, I think those Asian Americans who bucked against the model minority construct many first generation immigrants Asian parents pressure their children to fulfill could also be considered “survivors.” They survived “tiger parenting” in which Chang described parental love as “distinctively conditional.”

In his case, having “Survivor’s guilt” means he made it. He shattered the “glass or bamboo ceiling” that too often blocks how far an Asian can advance in the mainstream American workplace. He also broke through the self-imposed expectations by Asians themselves. I see how “Survivor’s guilt” can be used to describe surviving both barriers.

As a Vietnamese American, I’ve been craving to read more Asian American voices like Chang’s. He shared aspects of his life that felt familiar and distinctively Asian American. Those stories sparked pride and also some uncomfortable questions.

Work Alcoholism

Chang talks about how he lost himself in his work. He calls it a socially acceptable addiction. His work is tied to his Korean identity. Chang talks about how he was both ashamed and scared of his Korean-ness throughout his life. He wrote, “I wanted not to be me… work made me a different person, work saved my life.” (191)

He built his restaurant’s brand on challenging how Americans see Asian food. It is through working closely with his dad, who was his first investor and business partner, does he experience “the closest thing to therapy” (46). I know a lot of Asian Americans who work all the time, who bring it home, who share it with their family over mealtime, whose work is part of their identity. This is definitely true for me. After I finished my PhD in history, I decided to return to Seattle to work with my family in our Vietnamese newspaper. Adult children rarely get to spend quality time with their parents. I knew if I worked alongside them at the newspaper, I would get a lot of “quality” time, like Chang did with his dad.

When Chang wrote that work saved him, it felt so familiar. Is that out of passion for the work? Fear? How can work be particularly healing? And what does it mean that parts of the hard working model minority myth aren’t such a myth after all?

Authenticity and Racism in Cuisine

Other kids would make fun of the Korean food Change ate growing up. He said he would rather see a white person want to make kimchi than to disparage it because it felt foreign. Chang points out arguments about authenticity and cultural appropriation emerge often in the culinary world (78). Chang is known for designing cuisine that reflects a mix of cultural influences. While Chang thinks these debates are “boring” (and I completely agree), Chang points out that it’s racist when someone thinks it’s acceptable to pay $25 for Italian pasta and refuse to pay the same amount for Asian noodles, which Chang argues are essentially the same thing (212). What he doesn’t say is that even Asian Americans feel this way. I know many Asian Americans who will gladly pay $25 for European food while expecting that authentic Asian food must be cheap. Does that mean racism is also internalized by Asians? And do Asians need non-Asians to eat and make Asian food to validate our cuisine?

Romantic Partners

In a chapter called “Grace,” named after his wife, Chang spent a few paragraphs explaining why he married another Korean-American. It made me question why so many Asian Americans, whether they marry inside or outside their ethnicity, feel the need to explain how or why we choose our partners (206). The race of our romantic partners seems to be one way to demonstrate how Asian we are. Asians are most authentically Asian if they choose someone of the same ethnicity, in Chang’s case, Korean. They are still connected and signal pride in being Asian if they choose to be with an Asian of another ethnicity. If an Asian American woman chooses to be with someone white, that is sometimes even less surprising than if they choose an Asian partner. If an Asian American chooses to be with a non- Asian person of color (e.g., Black, Native American, Middle Eastern, or Hispanic), they are making a statement.

There is a lot of complexity. What are the expectations for and of Asian Americans in who we choose as our partners? For non-Asians, what do you think when you see a same ethnicity vs inter-ethnic Asian couple? An Asian Interracial couple? Many, Including other Asians, assume that my partner is not Asian. So I do feel a sense of smug pride when I am able to invalidate their assumptions by telling them I have been in a long-term relationship with a Korean national, which feels like validating my Asian-ness.

Eat a Peach also has lots of accounts of Chang modeling leadership. Here are some universally appealing examples:

- Apologizing. Chang talks about the rage he directs at his own employees. He hated being known for his anger. The memoir is full of remorse. A former staffer detailed the abuse inflicted by Chang in Eater, and felt his apology was not enough. Part of leadership means accepting that the other party doesn’t have to forgive you.

- Transparency. He doesn’t cover up how his thinking has evolved. In fact, Chang includes many of his original correspondence and drafts to demonstrate how his thinking has changed. For example, he acknowledges most of his references are about men, “It’s my truth, which is why I’m leaving them in here, but I wish that some of it were different.” (228)

- Risk taking. Chang has a lot of stories of experimenting and taking risks as a chef and as an entrepreneur. In crafting the menu for a new restaurant, he wrote: “The only unifying thread was that we were nervous about every single dish we served.” (82)

I much prefer real stories as a way to impart leadership lessons. The most “self-help” -ish aspect of the book was at the end, “33 rules for becoming a chef,” which could be applied to life in general.

The memoir form allowed Chang to acknowledge his many faults. I was left with the impression that Chang got away with wrecking a lot of abuse and cruelty onto those around him. I actually appreciate that he’s an asshole. Allowing Asian American assholes to publish memoirs signals a willingness for mainstream audiences to have an interest in a broader spectrum of multi-dimensional, complex Asian Americans.

In bucking against the Asian model minority stereotype, Chang demonstrates how there are different ways to be a successful Asian American while also eventually celebrating and promoting his Asian identity.

Chang doesn’t talk about being an Asian American role model. It was probably not on his list of aspirations. Ultimately, an Asian American who shares about their life publicly becomes a de facto Asian American role model.

As an Asian in America, I want to believe that my leadership will have influence beyond the Asian community. We need to have more Asian role models who non-Asians look up to as well.

Chang proves it’s possible, whether he wanted to or not.

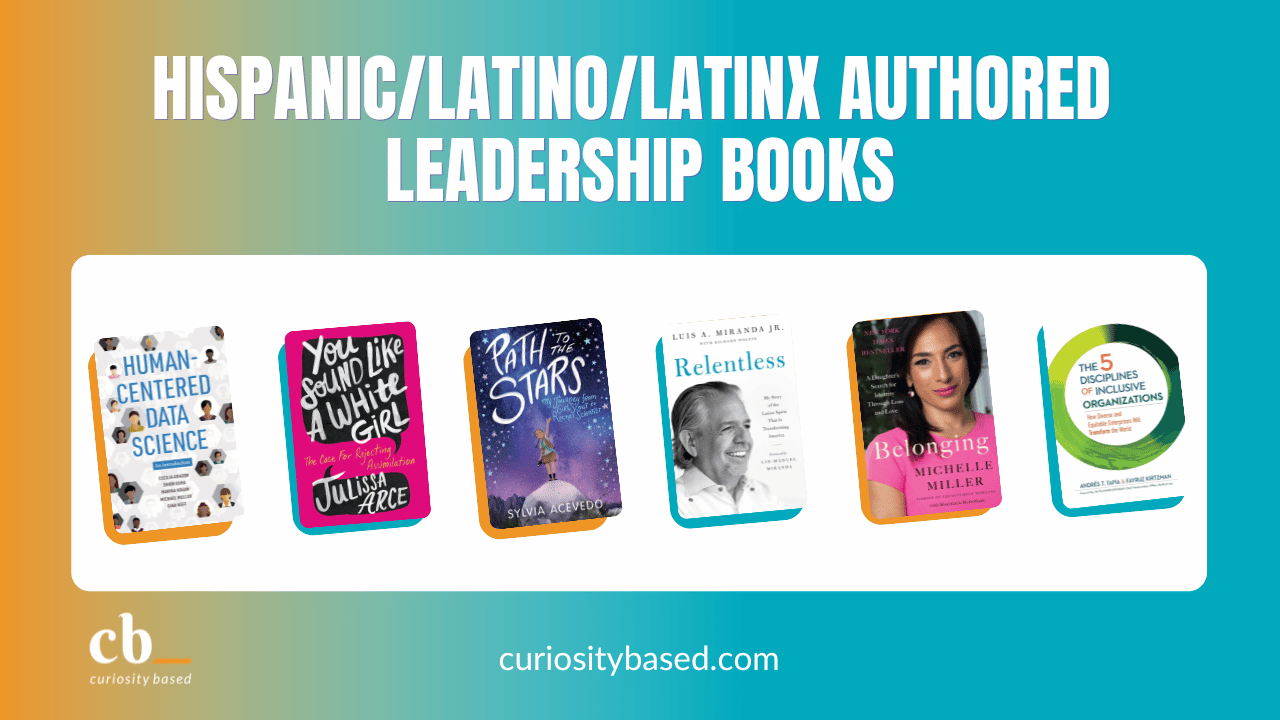

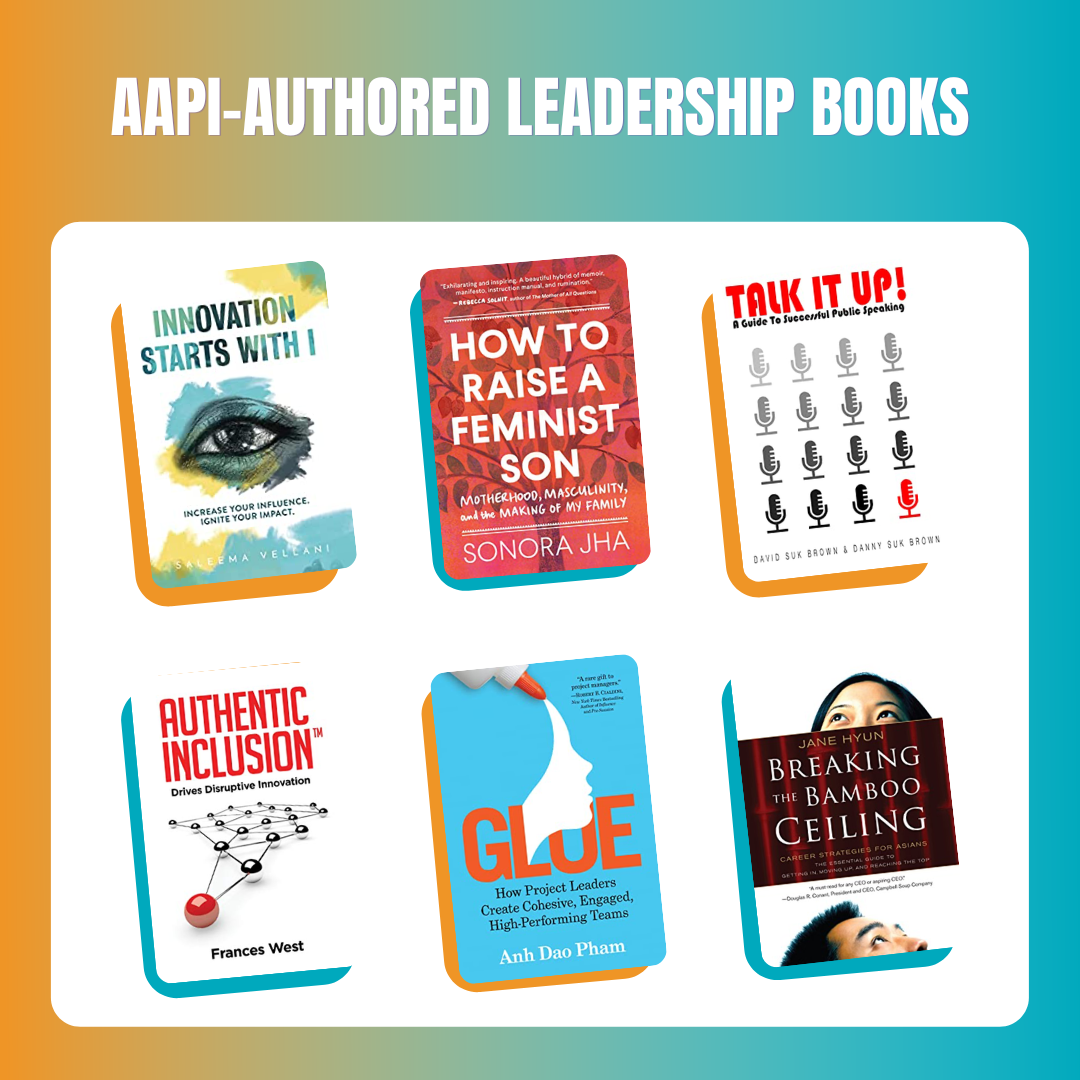

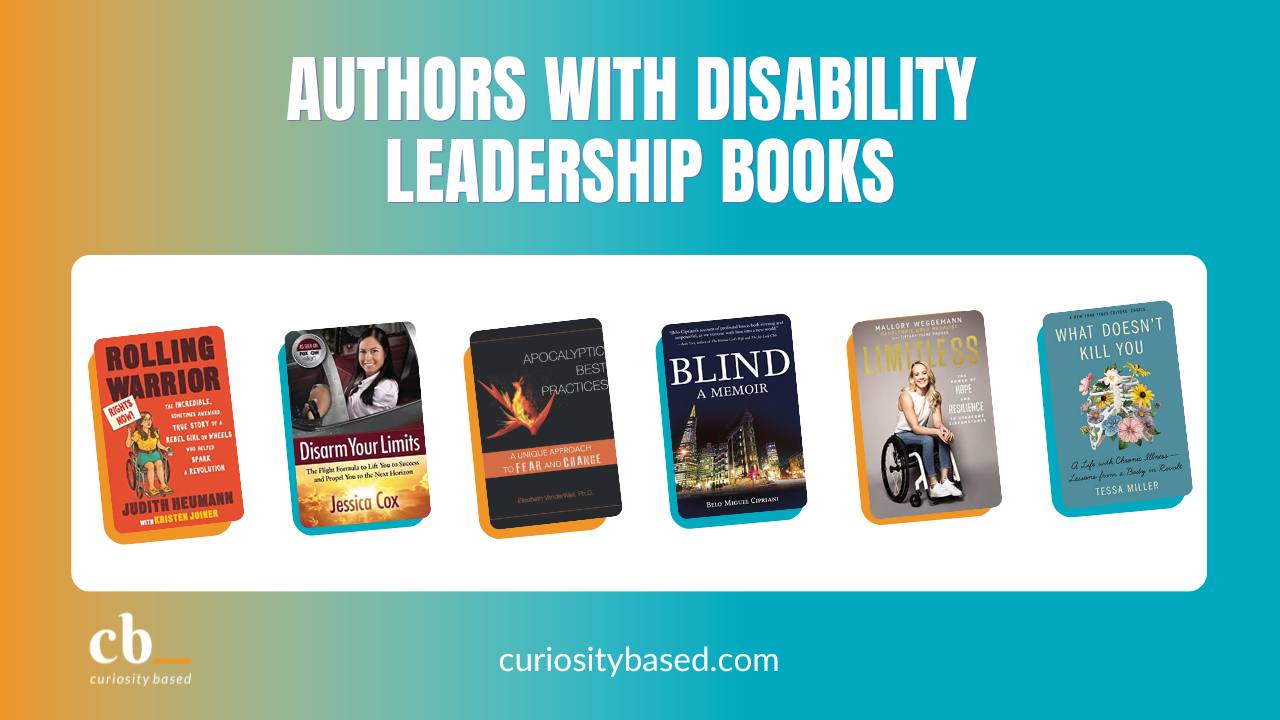

Interested in reading more? David Chang is featured on our AAPI-Authored Booklist!

Leave a Reply