I am in awe whenever I hear US politician and voting rights advocate Stacey Abrams speak. I knew I’d be inspired before I even started Abrams’ Lead from the Outside: How to Build Your Future and Make Real Change. But, I didn’t expect the part-memoir, part- leadership manual to be so practical, approachable, and relatable. Despite our very different backgrounds and life experiences, I could strongly identify with Abrams’ stories of self-doubt and anxiety.

There are few “how-to guides” to help those of us who are “other” or in the minority to become the ones in charge. She defines “minority leader” as “anyone who exists outside the structure of traditional white male power.” “Power and leadership are hard, and it’s especially difficult for those who start out weighed down by stereotypes and lack of access,” Abrams wrote in the introduction of the book. She goes on to say this is “a handbook written for our experiences and challenges -a means to become the minority leaders who own our power and change our worlds.”

There are topics and aspects of the book that have universal appeal and leadership application, not just for minority leaders. I’ll quote liberally from Abrams’ book to spare you from my paraphrasing.

Work Sheets

Every chapter ends with a worksheet of questions to answer. My favorite is the worksheet entitled “trying again” in which you have to note “when you have been tempted to pretend you know the answer.” The worksheets pose probing questions that make people reflect deeply on what they want.

Money Matters –

I found the chapter where Abrams shares how much she didn’t understand about managing her finances, even after graduating from law school and earned a high salary to be vulnerable and relatable. . In a country where most people don’t have more than $400 in savings, it’s not just Abrams’ advice that is valuable. Her admission of shame about money also matters. She wrote, “To get ahead of the problem, explore your personal relationship with money and the explicit and silent claims made on your resources.”

Limited resources

Abrams encourages creativity when faced with limited resources. I call this being “scrappy.” Abrams turns the lack of resources into an advantage: “one of the best things about being in the minority is the fact that limited resources often lead to extensive creativity.” “We can become conditioned to believe we must have the same assets, or worse, that whatever we have at hand is inherently inferior. But the creative ability of minority leaders lies in excavating the valuable in what is available.” No matter who you are, you can feel like you don’t have enough or you could use more. This lesson can apply to anyone, regardless of their resources.

Aside from these universal lessons, I found the book refreshing and deeply relevant to my own experience as a “minority leader.” As a Vietnamese-American woman and a refugee, there were so many parts that resonated with me deeply. I keep rereading passages because Abrams articulated how I and so many of my minority leader friends feel, in such clear, jargon-free prose.

Acknowledging ambitions

The need to express our ambitions is a constant theme of the book. Abrams writes, “It’s crucial to understand and internalize our very right to even be ambitious. Because, for too many of us, we are stopped in our tracks before we begin because we don’t believe we deserve to want more. And it is by wanting that we begin.” Abrams keeps her goals on a spreadsheet, as a way of “acknowledging in print.” Abrams talked about being asked about her future political aspirations by a reporter while running for governor in 2017. She knew she wasn’t “supposed” to openly say she aspired to become president and yet she decided to say it aloud. There was initial backlash about her audacity, but it was followed by public support. This chapter made me reflect on how often I refrain from saying what I want aloud out of fear I will sound too audaciously ambitious.

Minority fear– I have read a lot of good leadership books by white men and they don’t address or acknowledge what Abrams refers to as “minority fear,” presumably because it doesn’t exist for the majority of these writers. Abrams writes, “Fears about how our differences are perceived, about stereotypes that kept us back, about how our success begets more responsibility will never die. But once we are aware of them, we can work with them” (48). These words felt especially true: “the complexity of minority fear cannot be dismissed by saying ‘don’t be afraid’ or ‘let it go.’ Our trepidation is often grounded in stories we’ve heard (35).” There were so many times that all my other minority leader friends and I could do was commiserate and comfort one another in this shared fear. Even Abrams admits that she encourages people to be fearless in inspirational speeches. In this chapter, she fully acknowledges the normalcy of minority fear instead of being swept away as if it were trivial. The fear is the “permanent companion eating away at confidence, ambition, relationships, and dreams.”

Let your-light shine-Abrams writes about minority leaders having to “confront..a tacit call for meekness, to hide our light lest we become too noticeable and change the discussion” (135). To fit in, I have had to dim my light so that others don’t feel threatened, I’ve had to shrink unconsciously. I’ve talked to many friends who were the “only” or the “minority” in their workplace who had to dim their light to make other people feel comfortable. Abrams talked about an Advanced Placement English teacher who didn’t want her to use advanced vocabulary words in class, even though she was using the words correctly, lest it make other students feel bad.

Abram’s book shows how when you build something for a minority group, it can actually benefit the majority. Her book is an example of the curb cut effect, in which features designed for a minority then benefit a much larger group than the people they were designed for. The “curb cut” refers to how ramps were cut into the sidewalk for wheelchairs and now these curb cuts are part of standard sidewalk design.

The book was originally titled “Minority Leader” in the first edition. It makes a lot of sense that it was renamed to” Lead from the Outside” in the later edition. Even though it was built for “outsiders”, I can imagine insiders and those within the majority will find valuable leadership lessons and insight into what those who are outsiders have to face.

I hope Abrams’ book also inspires other “outsiders” to share their leadership lessons so that the general public can benefit.

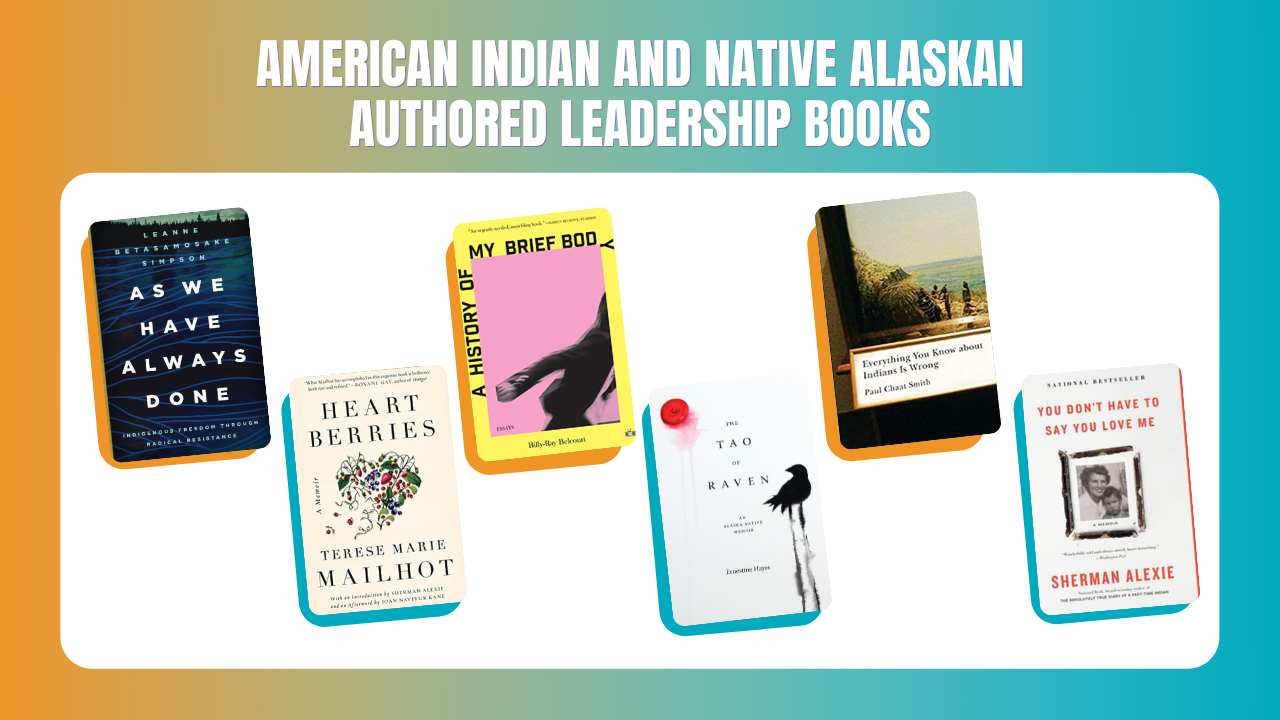

Interested in reading more? Stacey Abrams is featured on our Women-Authored Leadership Booklist.

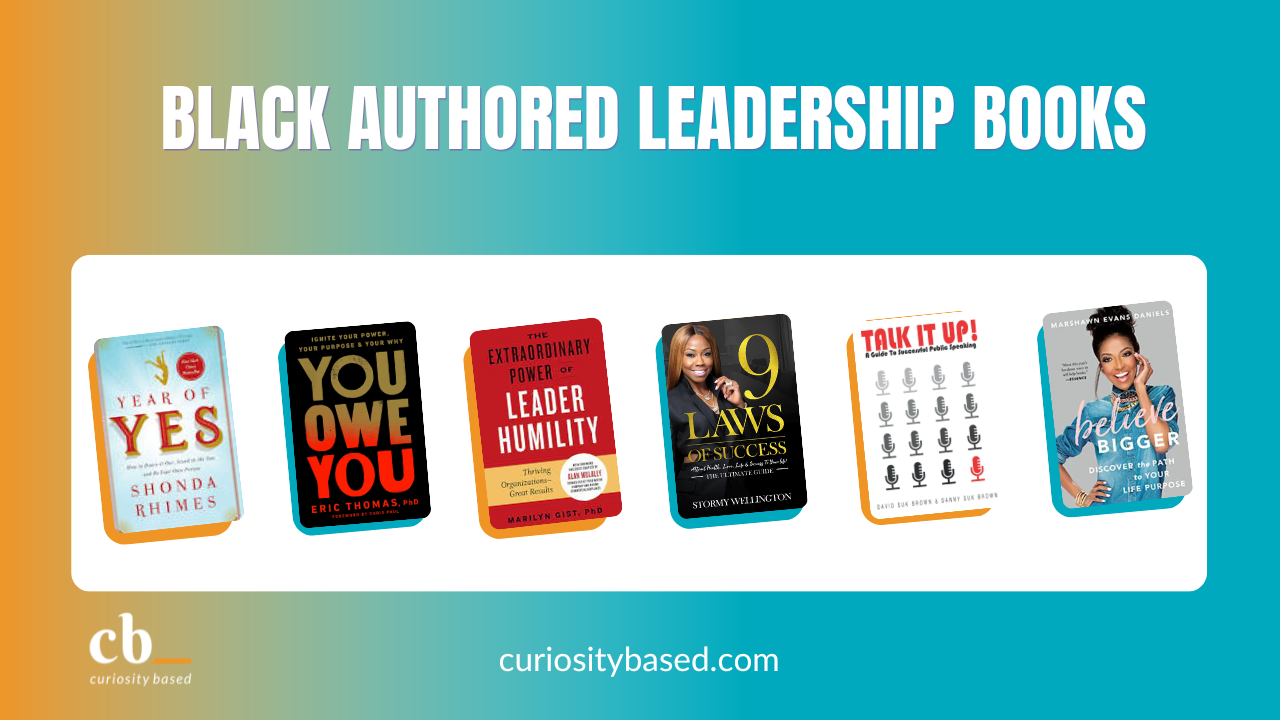

Stacey Abrams is featured on our Black-Authored Leadership Booklist!

Leave a Reply