What sparked your interest in serving in public office?

For me, it’s been a journey. I don’t know that I grew up thinking “I’ll be in public service.” Coming to the US as an immigrant from Hong Kong in the mid-70s, I always felt inherent gratitude that we were sponsored by my uncle to get education in college. In the mid-70s, Vietnamese refugees came to the US and one of my best friends in middle school was from Vietnam. The whole quest or interest in public service, whether volunteering or rolling up sleeves to solve problems, was always a part of me.

I pivoted from working in private agencies after I left college to the Port of Seattle and it really opened my outlook into what public service looks like. The Port of Seattle is a public government agency that’s baked in economic development with a huge interest in creating an inclusive economy and not leaving people behind as we create opportunities in the region. Along the way, I went back to school and got a public service degree 20 years later from the UW Evans School of Public Administration.

[It sounds like achieving inclusion and belonging are strong motivations for you.]

As a Bellevue Councilmember, a sense of belonging very much resonates. Our motto is “Bellevue welcomes our world and diversity is our strength.” We need to be a place where people feel like they belong. For Asian Americans, if they don’t feel like they belong, they might always feel like a perpetual foreigner.

What is it like being a woman in public office? What are some strengths and challenges you experience that might be unique for women in policy-making spaces?

Public office brings challenges and joy as well. For me, I have to wonder if it is only my perspective as a woman that I have a certain lived experience. Or is it because I am both a woman and person of color, an engineer, and in a biracial marriage? I wonder if it would be different if I was an elected male of color, versus an elected woman of color. One of the challenges is that we can’t pull apart our identities. We can’t play the “what if” game. When I’m in spaces where there are predominantly men, whether it’s in policy or in my engineering management career, there are not really as many people who look like me. I do believe that women are still treated differently than men from the patriarchy standpoint. We can show up with similar mannerisms, the things we say and how we say them, and we are judged differently. If I say something and don’t get feedback and then have a male colleague who says exactly the same thing, they’re suddenly getting an interactive dialogue. In a way, that’s the most insidious part of the disparities. We may never be able to put our finger on it because bias is so subtle. Lastly, as an Asian, I also wonder if we’re really hard on ourselves because of the “model minority” stereotype and the idea that we don’t want to shame our parents because they sacrificed so much for us to live the American dream. We can show up with perfectionism and are more mindful of how much we lift up our voices.

There are three different hierarchies: class, gender, and race. I think about the fact that the large parts of my career and ever since I came to the US, my dad had the belief that we need to speak English perfectly and lose our accents. The pathway to success meant to assimilate. When I think about the hierarchy, I find it to be very true. In the male dominated engineer space, I found that I had to put away a part of me to fit in. Later in my life, I shied away from conformity and began to really center the voices who weren’t being heard in public spaces and to lift the voices of women and minorities. It led to innovation with diverse thoughts and new ideas.

In some regards, our society is a system of systems. The way it works is that if you fit inside the system, you don’t get kicked out as an outlier. It’s a delicate dance. We are trying to change the system from within the system that is kicking us to the curb. For me, I was never someone who felt comfortable being an activist, probably because my dad had the belief that we had to keep our head down and be humble and not make waves. He was born in China and back then if you were a government official or successful in business, you could be sent to a reeducation camp. My whole family fled. The lesson learned was “don’t make waves or bad things will happen to you.” Despite this, we have found a way to change the system from within the system to try and make changes. It can feel slow and frustrating. Often, you’re gas lit and left wondering if your lived experience is valid or not. We don’t talk openly about it enough.

From your perspective, what are the most pressing issues to our region?

They’re all interrelated. Certainly in our region, in Bellevue and nationwide, affordable housing is huge. That leads to all kinds of various things, including homelessness, or lack of transportation choices for people. It leads to change of our environment and people who are most far from the resources living in spaces where there’s less green space and parks. Those system inequities also play into the broken, underfunded systems – like what we saw with COVID through healthcare access and economic opportunities.

I believe in inclusive economies. Who is surviving during COVID? – The big companies. Small mom and pop shops are struggling. We’re also seeing a disparity in who has a voice at the table and who’s facilitating the meetings being held at those tables.

Those pressing issues are grounded in who is in leadership that is willing to make the kind of changes needed to step away from the status quo and to step into that scale. Maybe we have done a little more with homelessness, transportation, economy, etc, but baby steps won’t get us into where we need to go anytime quickly. Instead, we are getting farther and farther behind. In Bellevue, the average price of a home is over $1 million. Rents in some of the smallest rentals are still at $2000. How much money do you need to make to survive on that kind of wage?

Mental and behavioral health services are also underfunded and part of a broken system. As a society, we have continued to treat the non-profit, community-based organizations as though people should love the work they do so much that they don’t need to have a living wage. That is wrong and unsustainable. We have to reckon with the fact that the very people who are working in these broken systems are not making a living wage yet are doing the hardest work to meet community needs. If we don’t change the ways we think about funding these organizations, we will exacerbate challenges. When you get on an airplane, you put on your own oxygen mask before helping others. Nonprofits are not getting the oxygen masks that they need.

What are some policy solutions that you’re particularly passionate about?

From a leadership standpoint, we need leaders who have the courage to speak truth to power and state what needs to change. At the same time, we need to give our community a voice and help to let them be advocates. We need more engagement with our youth. We need to lift community voices and organizations so that they understand how budgets are built, where the gaps are, where the changes are needed to make funding.

I’ve heard from others that we need to give people a place at the table. What we really need to do is bring people in to build a table together and engage in co-creation. We need to rethink the very way that government provides services and how we are grounded in “people first” to focus on what people need versus what we think they need.

The other part is that when we talk about challenges around housing, transportation, environment, and economy – they don’t stop and city borders. We need to get as regional as possible to collaborate and find solutions together.

How does curiosity aid the policymaking and decision making process?

If we want to have innovative solutions, curiosity is foundational. In addition to that, if we center things from a space of curiosity, it also creates a better entry point for conversation. I was trained as an engineer. I have a lot of curiosity and ask a lot of questions. Asking questions can be perceived as challenging someone’s work. Centering spaces with curiosity can lower the temperature in the room. We want to understand the thinking process behind policies. It’s about centering our ability to learn, versus a perception that we’re just criticizing someone’s sense work.

I’m naturally curious and it helps me learn and understand. It makes the decisions better. I have to say that it took me a while to get to that space where as a curious person, I didn’t see that there were issues asking questions. Once I got into leadership, management, and then council, I had to start with the framing of natural curiosity so that I was being proactive in explaining the ‘why’ behind my questions.

If we put out a policy that only addresses the ‘tip of the iceberg’ about what problem we’re trying to solve, you don’t get down to the root causes of the issue. The policy and solution you bring may make underlying causes worse. We can see it played out in homelessness policies. If we ask the ‘why’, it helps us to get more grounded in what problem we’re trying to solve.

Continue reading our Women in Political Leadership Series:

- Senator Yasmin Trudeau

- Representative Debra Entenman

- Redmond Mayor Angela Birney

- Seattle Deputy Mayor Kendee Yamaguchi

- Seattle City Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda

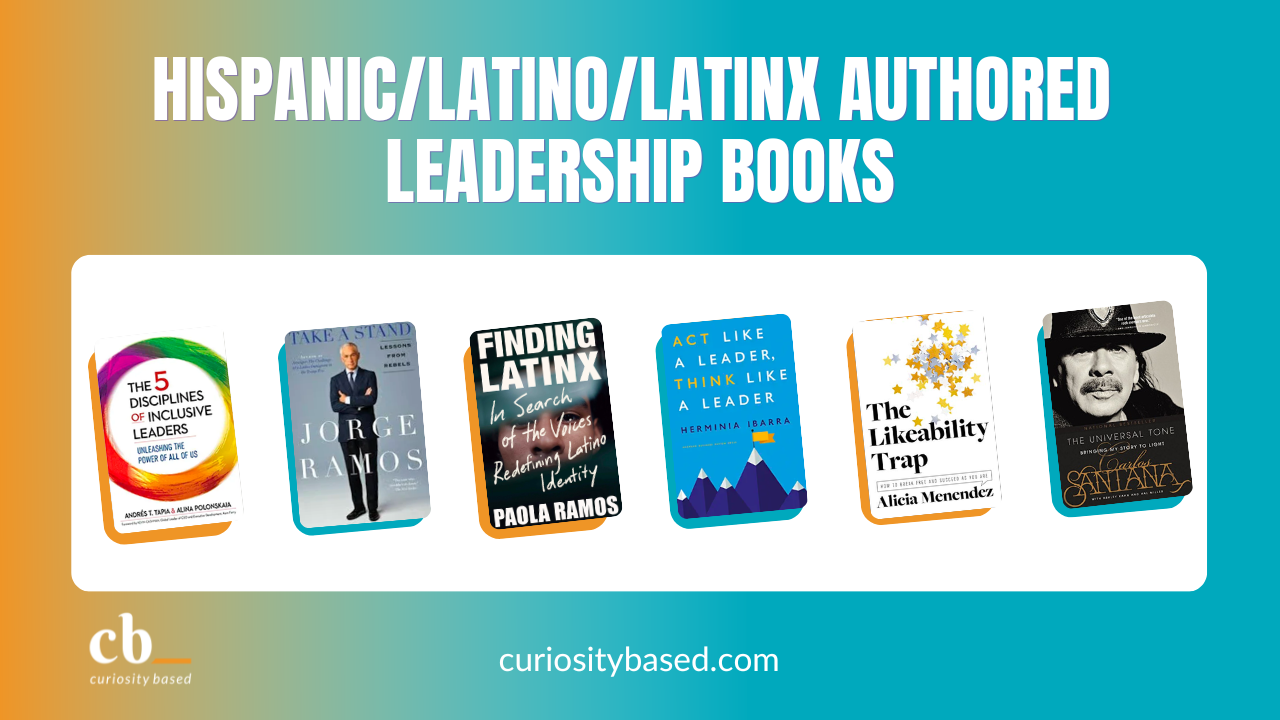

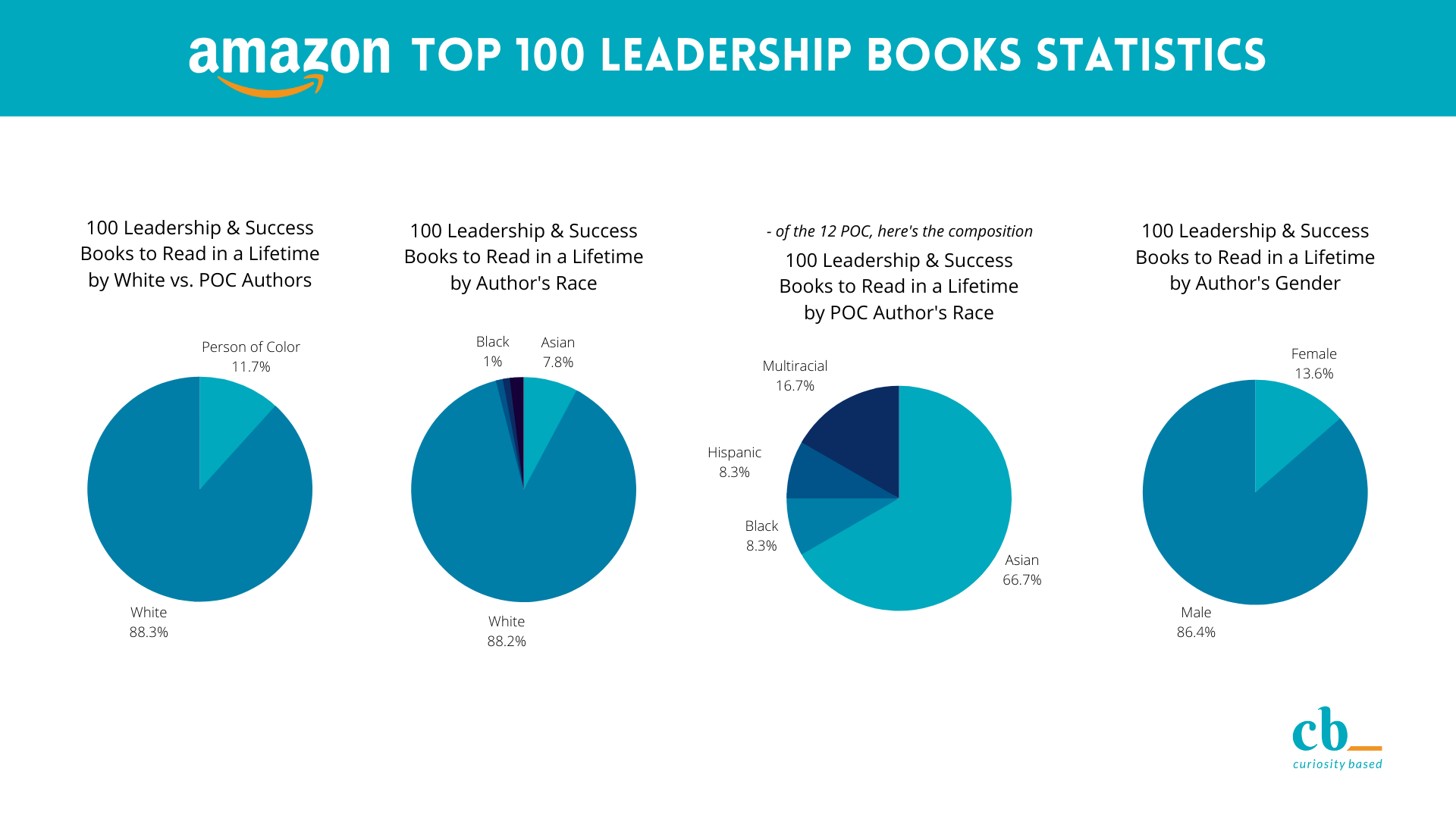

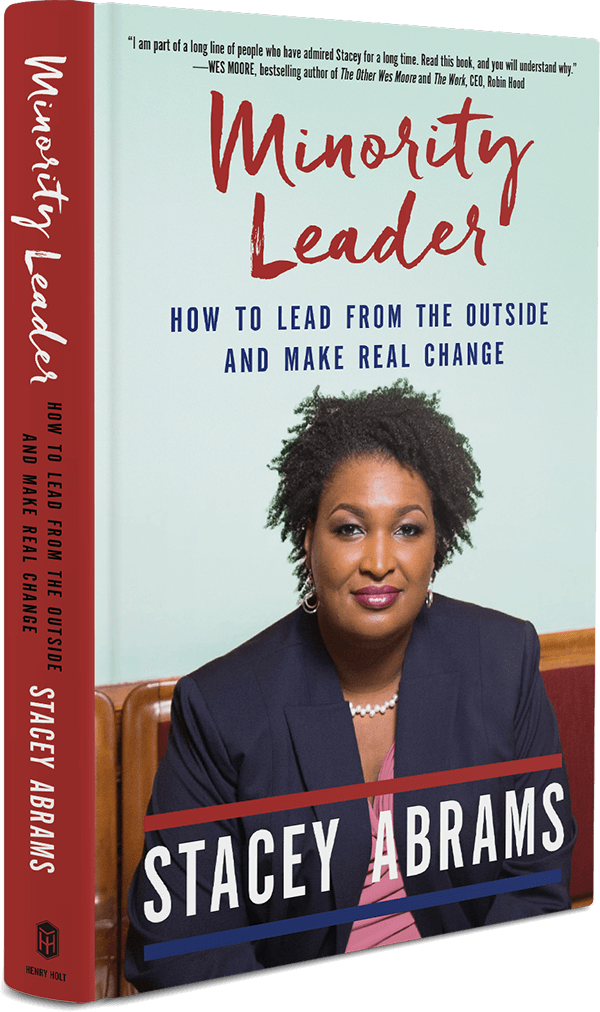

Interested in learning more from women in leadership? Check out our Leadership Book List, where we have compiled 350+ books written by women in leadership.

Leave a Reply